On tap this month are:

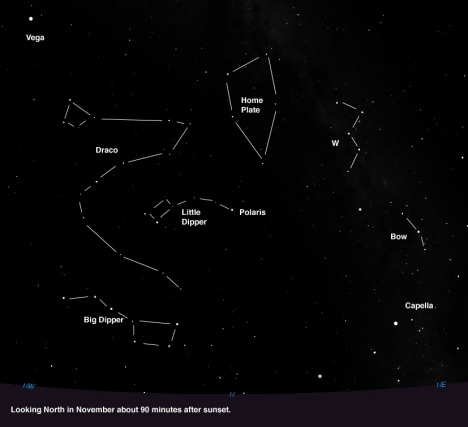

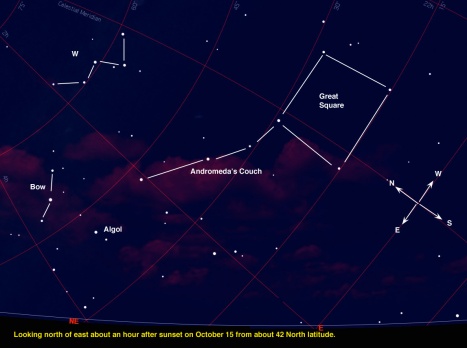

To begin our monthly exploration of the night sky in the east, you can take a slide down Andromeda’s Couch to Mirfak and the Bow of Perseus in the northeast – that is, you can if you learned how to find Andromeda’s Couch last month. If that’s new to you, ignore it for now and simply start by looking for the “Bow” of three bright stars rising low in the northeast.

To find it, go out about an hour after sunset and watch the bright stars emerge. It may take a few minutes to see the bow clearly, but what you are looking for is three stars in a vertical arc, with the middle one – Mirfak – the brightest. How big an arc are we talking about? Just make a fist and hold it vertically at arm’s length, and your fist should just cover these three stars. How high? The bottom one should be about a fist above the horizon. Here’s a chart modified from Starry Nights Pro software.

-

Click image for larger version. (Derived from Starry Nights Pro screen shot.)

Click image for larger version. (Derived from Starry Nights Pro screen shot.)

For a printer friendly version of this chart go here.

The bow asterism is the core of the constellation Perseus. Now if you want to be a stickler about mythology, Perseus usually is not depicted with a bow – he wields a sword instead, which he is holding in his right hand high over his head, while in the left hand he holds the severed head of Medusa. Here’s how the 1822 “Urania’s Mirror” depicted him.

- Perseus – click for a larger version.

Oh boy – and if you can see all that in these stars, then you have a very vivid imagination. I never would have learned the night sky if I had to try to trace out these complex constellations as imagined by ancient cultures and depicted in star guides up until fairly recently. And for the purposes of helping you find your way around the night sky I think remembering the “Bow of Perseus” is easier.

Getting sharp about brightness

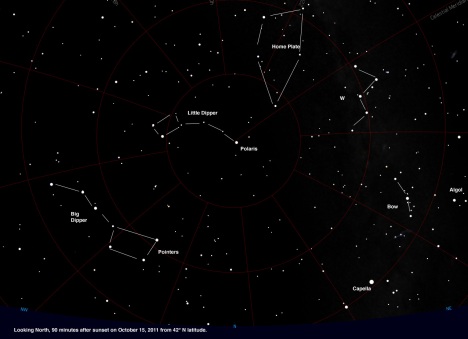

As you start to learn the stars, it may surprise you how precise you can be about their brightness. At first you may have difficulty just telling a first magnitude star from a second, but if you get to know Algol, the “Demon Star,” I bet you’ll find that you can quickly become quite sophisticated in assessing brightness and shaving your estimates down to as little as a tenth of a magnitude. So let’s take a closer look at the Bow and three bright stars in this region – Mirfak, Algol, and Almach.

Imagine a star that regularly varies in brightness every few days – that’s what Algol does. Exactly every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes it begins a 10-hour period where its brightness dims more than a full magnitude. If you look during the right two hours, you’ll catch it at or near its dimmest – and most of the rest of the time you’ll catch it at or near peak brightness. And it’s quite easy to judge. But first let’s find it. Here’s the chart we’ll use.

Notice how Algol makes a very nice triangle with two companions, and all three stars are close to the same brightness – Almach, the northern-most star in Andromeda’s Couch; Mirfak, the central star in the Bow of Perseus; and Algol. Algol is called the “Demon Star” because it varies in brightness – and, of course, it marks the head of Medusa. Gazing directly at her turned onlookers to stone according to Greek mythology – but I hope that doesn’t worry you because I’m going to ask you to stare directly at her – or at least at Algol! In fact, that relates to our first challenge: Go out any clear night and study these three stars and decide which is the brightest. Two are equal in brightness, but one is a tad brighter than the other two. Which is it? Algol? Mirfak? Almach? (The answer is at the end of this post so you can ignore that answer until you actually have an opportunity to test yourself.)

However . . .

Because Algol is a variable, sometimes when you look at it, Algol will actually be significantly dimmer than either Mirfak or Almach. In fact, there’s a reasonable chance it will be dimmer than either of Mirfak’s two fainter companions that make up the Bow of Perseus. If, when you test yourself, this is the case, congratulations! Make note of the date and time. But that’s not the test – just fun! For the test you want the “normal” condition, which has these three nearly the same in brightness.

OK? Back to Algol. It’s a special kind of variable star known as an eclipsing binary. That is, what looks like one star to us is really two stars very close together, and when we see Algol’s light start to dim it means its companion is passing between Algol and us causing an eclipse. Since the stars are locked in orbit around one another this happens with clockwork regularity.

The above diagram came from this astronomy class web site which includes a more detailed scientific explanation. Since either star of the pair can cause an eclipse, there is a much fainter, secondary eclipse of Algol – really too faint to be noticed by most observers. Why is one eclipse fainter – because one star is blue and much hotter/brighter than the other star. It is when the cooler star is in front that we see the dramatic change in light.

It’s fun to catch Algol in mid eclipse, but I suggest you not read about when to do this right now. Instead, do the little challenge first. Then when you’re ready, go to the final item in this post, which explains how and when to catch Algol in eclipse and in the process, tells you the brightness of its companions.

See a few hundred billion stars at one glance!

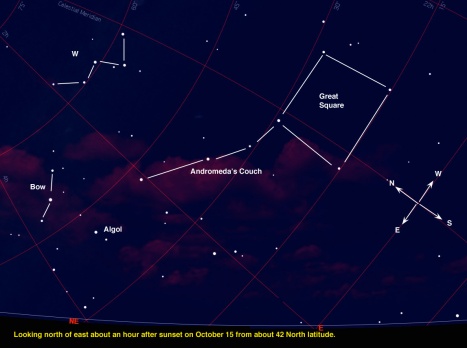

Yes, you can do it if you have good dark skies, you have allowed your eyes to dark adapt, and you are looking at the right place. Once again, Andromeda’s Couch is our guide, and what we are looking for this time is the Great Andromeda Galaxy aka M31.

This is our “neighbor” in space if you can wrap your mind around the idea that something “just” 2.5 million light years away is a “neighbor.” As you try to do that remind yourself that a single light year is about 6 trillion miles – of course, good luck if you can imagine a trillion of anything! OK – let’s try that – quickly. If you wanted to count one million pennies, and you counted one every second, it would take you 11 days. A billion pennies would take you about 31.7 years! And a trillion pennies? 31,700 years – roughly the time that has elapsed since the earliest cave paintings. So what if you were the cabin boy on an inter-galactic spaceship charged with ticking off the miles at the rate of one mile a second on the way to Andromeda? Think you could do it? Think you would live long enough? Hardly! The task – and journey – would take you almost half a million years – or by my crude estimate 475,650 years! And that’s non-stop counting. Ohhh – are we there yet, Mom?

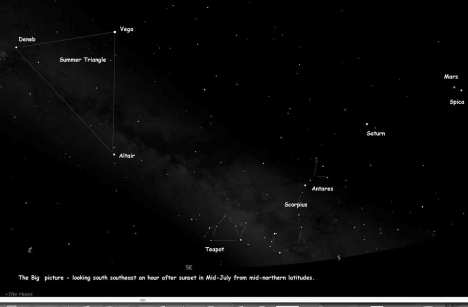

And yet here you are collecting photons in your backyard that got their start on the journey to your eyes some 2.5 million years ago! Even if you live under normal, light-polluted skies, you should be able to see the Andromeda Galaxy with binoculars. In fact, this is one object where the binocular view can be as rewarding as the view through a telescope. Here’s a wide field chart for mid-month and about 90 minutes after sunset. At that point the galaxy should be roughly half way up your eastern sky. (Look for it on a night when the moon isn’t in the sky and when, of course, your eyes have had at least 15 minutes to dark adapt.)

- Click image for larger version.

Starting with the preceding chart – and moving to the chart below, here’s a more detailed star-by-star hop to the Andromeda Galaxy:

- Locate the Great Square

- Locate Andromeda’s Couch off the northeast corner of the Square.

- Go down to the middle star in the couch, then count up two stars and bingo!

- You can also find the general vicinity by using the western end of the “W” of Cassiopeia as if it were a huge arrowhead pointing right at the Andromeda Galaxy.

Well, “bingo” if you have been doing this with binoculars. With the naked eye it’s more an “oh yeah – I see it – I think!” But what do you expect? Think about it. The light from the near side of this object started its journey about 150,000 years before the light from the more distant side did! And think of where the human race was 2.5 million years ago when these photons began their journey – or for that matter, where all these stars really are today! Nothing is really standing still – everything is in motion.

You might also want to think about the folks who are on a planet orbiting one of those stars in the Andromeda Galaxy and looking off in our direction. What will they see? A very faint patch – certainly fainter than what we see when we look at the Andromeda Galaxy, but in a modest telescope roughly similar in shape, though about two-thirds the size. Both Andromeda and the Milky Way Galaxy we inhabit are huge conglomerations of stars. We’re about 100,000 light years in diameter – Andromeda is about 150,000 light years in diameter. The Milky Way contains perhaps 100 billion stars – the Andromeda Galaxy maybe 300 billion. (Don’t quibble over the numbers – even the best estimates are just estimates. )

And yes, in a few billion years we will probably “collide” with the Andromeda Galaxy, for we are hurtling towards one another. Such galaxy collisions are not that unusual and probably aren’t as violent as the word “collision” makes them sound – but they do, in slow motion, bring about radical changes in one another.

But all that is for the professional astronomers to concern themselves with – for us, there’s the simple beauty and awe of knowing that with our naked eye – or modest binoculars – we can let the ancient photons from hundreds of billions of stars ping our brains after a journey of millions of years.

So here’s hoping for clear skies for you so you can find a winking demon and capture in your own eye the photons from a few hundred billion stars in the Andromeda Galaxy!

And now the truth about Algol and companions

Have you done the Algol test yet? Looked at Algol, Mirfak, and Almach and tried to decide which is brightest? If so, you can check your answer by continuing to read. If not, I suggest you first do that exercise, then come back to this.

Chances are that when you look at Algol, it will be at its brightest – but how can you tell? Well, as we mentioned, you can compare it to Mirfak – but there’s an even closer match with another nearby bright star – Almach. That’s the third star in Andromeda’s Couch – the one nearest Algol.

Mirfak is the brightest of the three at magnitude 1.8.

Almach is magnitude 2.1 – which is the same brightness of Algol when Algol is at its brightest – which is most of the time. OK – for the hair splitters, Almach is a tad dimmer than Algol, but the difference is far too little to be able to tell with your eye. But that makes Mirfak about one third of a magnitude brighter than the other two. That difference you should be able to see – but it does take practice.

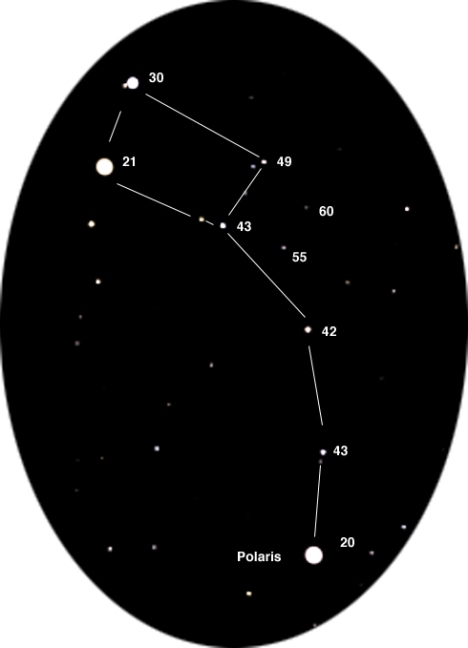

Here’s a chart showing the magnitude of the stars near Algol that you can use to compare it to and see if it is going through an eclipse. People who look at variable stars use charts like this, but with one important exception – the numbers are given like they were whole numbers so you will not confuse a decimal point with another star. Thus, a star like Mirfak, of magnitude 1.8, would have the number “18” next to it. I broke a convention here because there are just a few bright stars on the chart, so I didn’t worry about the possible confusion of a decimal point being mistaken for another star.

So If Algol and Almach are the same, no eclipse is going on at the moment. If Algol appears dimmer than Almach, then an eclipse is in progress. If it’s as dim or dimmer than either of the companions of Mirfak in the Bow, then you can be pretty sure you’ve caught Algol at or near its darkest. In two hours – or less – it will start to brighten and will return to full brightness fairly quickly.

Catching Almach at its dimmest is fun, but not as easy as it may seem. Why? Because although an eclipse happens every few days, it may happen during the daylight hours, or in the early morning, or some other time when it’s inconvenient. And, of course, you need clear skies. So when I want to observe an Algol eclipse, I go to a handy predicting tool on the Web that you can find here.

I then note the dates and times and pick out only those dates when the times are convenient to me – that is, happening during my early evening observing sessions. Then, given the iffiness of the weather, I consider myself lucky when I get a good look at an eclipse of Algol. What are your chances – given your weather – that it will be clear on a night when an eclipse is visible before your normal bed time?

Algol starts to noticeably dim about two hours before mid-eclipse and is back to almost full brightness two hours after mid-eclipse.

Using the Sky and Telescope Algol calculator for October 2014 I find that just one hits at a good time for me – October 13, 9:25 pm EDT

Of course the dates and time may be different for you, depending on where you live, and none of us can escape the whims of the weather!

Filed under: 1. Month-by-month, j. October, Uncategorized | Leave a comment »