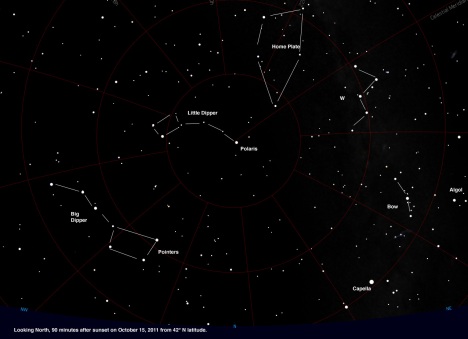

For a printer-friendly version of this chart, click here.

When I say “really bright,” I mean Capella – and I say it because so many folks assume, quite understandably, that the North Star will be the brightest in that section of the sky. It isn’t.

Capella is one of our brightest stars, and you may catch it this month just peeping up over the northeastern horizon about an hour and a half after sunset. And it is brilliant! When you see Capella, compare it with the North Star and you will get a good idea of what the word magnitude means. There are a solid two magnitudes difference between the two – or if you want to get technical, Capella is magnitude 0 and Polaris is magnitude 2.

Yes, the magnitude system goes backwards – the lower the number, the brighter the star. Each magnitude difference represents a change of about 2.5 times in brightness. So a zero magnitude star is 2.5 times as bright as a first magnitude star – and 2.5 x 2.5, or 6.25 times as bright as Polaris, a second magnitude star. And while we’re on this subject, the faintest star in the Little Dipper – it’s over in one corner of the cup – is just about magnitude five. That means Capella is 100 times as bright as that star. (OK – if you actually do the math it doesn’t come out because I rounded off the difference – it’s really 2.512 for those wanting more precision.)

In fact, there is another interesting way to look at that star – at magnitude 4.9 it is almost exactly what our Sun would look like if it were placed just 32.5 light years away. At that distance our sun would be magnitude 4.8 – and that distance is the distance we use to compare stars. That is, to get an “absolute magnitude” for them so we can compare apples with apples, we ask ourselves how bright a star would be if it were 32.5 light years from us.

And while we’re on the subject of magnitude, the Little Dipper does give us a great range. Polaris, as we said, is magnitude 2. The other bright star in the Little Dipper is magnitude 2 also – it’s at the end of the cup away from Polaris. Sharing that end is a magnitude 3 star, and these two are known as the “Guardians of the Pole” as they are prominent, close, and like other stars, circle around the pole every 24 hours. Most of the other stars in the Little Dipper are magnitude 4, with the one star in the far corner of the cup being magnitude 5, as noted – well, actually 4.9. There’s a chart with these magnitudes in this post. Many people who live in light-polluted areas can see only three stars in the Little Dipper – Polaris and the two Guardians of the Pole.

How faint a star can you see? Depends upon your eye sight, the light pollution in your area, the transparency of the skies on any given night, how high the star is in the sky, and, of course, your vision and dark adaption. But as a general rule of thumb magnitude 6 has been accepted as the typical naked eye limit. However, if you live in a typically light polluted suburb you may see only to 4, or worse yet, magnitude 3. And observers on mountain tops with really clear skies reliably report seeing stars as faint as magnitude 8. All of this is with the naked eye. Add ordinary binoculars and you will certainly add three to five magnitudes to the faintest star you can see. In fact, you take a huge jump in the number of stars seen just by using binoculars with 50mm objective lenses. That’s why many amateur astronomers with fine telescopes also are likely to have a pair of 10X50 binoculars that they keep handy. I always did, but more recently I stumbled upon some very inexpensive Celestron 15X70 binoculars that I love for quick peaks, though they are two powerful and large to hold steady for serious observing.

For more serious work I now use relatively expensive 10X30 image stabilized binoculars. Yes, the 30mm means they do not gather nearly as much light as the 50mm standards – but the image stabilization means they take better advantage of the light they do gather. They’re also more compact and light, so I don’t mind carrying them for several hours.

Capella will be a “look east” guide star next month, but you can get to know it this month as you look north. And if you live in mid-northern latitudes, it will become a most familiar site. In fact, where I live – about latitude 42°N – it is in the night sky at some time every night of the year. This is because it is so far north that as it circles Polaris, it only dips below the horizon for a few hours at a time.

Filed under: 1. Month-by-month, j. October | Tagged: Capella, Little Dipper, magnitude explained, North Star, Polaris | Leave a comment »